VERTAALD MET GOOGLE VERTALEN !

Google Translate of Google Vertalen is een gratis online vertaaldienst van Google. Het biedt automatische vertalingen aan tussen een groot aantal volkstalen.

Google Translate of Google Vertalen is een gratis online vertaaldienst van Google. Het biedt automatische vertalingen aan tussen een groot aantal volkstalen.

Business quarrels Willem Blijdorp is a media-shy but celebrated entrepreneur who is widely praised for his business successes. A trail of lawsuits and ruined ex-business partners tell a different story. "I feel business-like murdered by Blijdorp."

'I am a farmer's son from the Noordoostpolder.' On 20 November 2021, near-billionaire and entrepreneur Willem Blijdorp will start his speech in the auditorium of Nyenrode, visibly uncomfortable in the red-gold cape that he will be given as a brand new honorary doctor. The ceremony is part of celebrating the 75th anniversary of the 'Business University in Breukelen.

The eulogy on the 69-year-old trader in duty-free articles comes from Kitty Koelemeijer. She is a professor of Marketing at Nyenrode and supervisory director of Blijdorp's listed trading house B&S Group. Koelemeijer tells the approximately two hundred attendees about the "extraordinary achievements" of Blijdorp as an entrepreneur and how important "sharing success, philanthropy and benevolence" is to him.

In the acceptance speech, Blijdorp outlines how his trading house B&S Group, listed on the stock exchange since 2018, has an annual turnover of around 2 billion euros. Customers from all over the world, from the U.S. government to China's Alibaba, order what they need from B&S, from spirits to consumer electronics. He also has an edifying message: "There is a moral obligation to make something of it together, to keep everyone involved. I am the figurehead of B&S, but in the end, it's all about treating each other fairly."

These are fine words from the media-shy and virtually unknown entrepreneur to the general public – a man with a nose for business, who makes deals everywhere, sees trade, and dares to take big risks.

NRC published at the beginning of this year about a business conflict that got out of hand in Blijdorp, in which tens of millions are at stake. In recent weeks, the newspaper further investigated the past of the duty-free entrepreneur and traced many lawsuits, disappointed and destitute former business partners, and allegations (and reports) of theft, intimidation, and threats. They tell the story of a man with two faces who quotes less experienced entrepreneurs and then mercilessly discards them – and runs off with their business and goods.

Butterfahrten

After his studies at the Hotel School in Maastricht, Willem Blijdorp and fellow student Jacques Streng found a job at the Groningen shipping company Kamstra in the mid-seventies. It organizes the popular Butterfahrten from Eemshaven: boat trips outside territorial waters, where Dutch and German customers stock up on duty-free goods en masse. First, it concerns butter (hence: Butterfahrt), later mainly drinks, cigarettes, perfumes, and shampoos.

Blijdorp and Streng quickly make a career and took over the shipping company after a few years. Streng takes care of the boats, and Blijdorp focuses on purchasing luxury goods. This puts him in lucrative 'parallel trade', the import and export of branded goods that are marketed much cheaper in one country than in another. In the Groningen Farmsum, Blijdorp has sheds and a transshipment center built for this purpose.

Business is going well, and Blijdorp has been investing in real estate since the late seventies – including in prostitution buildings in the Groningen city center, according to cadastral deeds. Het Nieuwsblad van het Noorden describes him in 1982 as one of the two "most important pawnbrokers in the Groninger Nieuwstad" – the place where window prostitution is concentrated.

Business is going well, and Blijdorp has been investing in real estate since the late seventies – including in prostitution properties in the city center of Groningen.

The reason for the attention is a conflict about renovating a prostitution building of Blijdorp and a business partner. On the ground floor, "bathing areas and beds surrounded by mirrors took shape, while the six elderly and two students above try to observe hygiene in a shower room usually only found on old, overcrowded campsites", writes het Nieuwsblad.

In 1987, a business partner says in the same newspaper that he owned 37 chambers crib-house in Groningen rented out exclusively for prostitution but did not elaborate on Blijdorp's importance. Blijdorp holds his interest in prostitution premises until 2010. During that period, he is also a shareholder in companies that trade DVDs. Two of them, the erotic mail order company Solidare from Emmen and the Butterfly Erotic Club, figured between 1999 and 2006 in dozens of lawsuits of customers who feel that their unjustly expensive subscriptions have been sold. Trade then dries up, but the companies still exist.

Blijdorp spends most of his time on international trade, in cigarettes, for example, which he brings from Eastern Europe to his transshipment center in Farmsum. There is a hint of fraud around the business.

For example, in the early nineties, the name of one of his companies appears in Czech court documents about cigarette smuggling and payment of bribes to a local customs officer. Blijdorp's company escapes criminal prosecution and only receives an additional levy.

In 1995, the Dutch investigation service FIOD invaded the warehouses of Blijdorp, where eighty people worked. One of the suspicions: is the evasion of excise duties on tobacco products. The case is dropped and Blijdorp continues to build his empire. Blijdorp, who explains to the Nieuwsblad van het Noorden that he mainly trades in "semi-excise goods", turned his company into a wholesaler in the nineties. The sale of tax-free items to consumers has had the longest time due to European unification. The same goes for the Butterfahrten, with which he amassed his first fortune.

After the turn of the millennium, Blijdorp is building a new flagship. Thanks to mergers and acquisitions, his B&S Group (named after Blijdorp and Streng) is growing into a large, international trading house, which will go public on the Amsterdam stock exchange in March 2018. Blijdorp owned (and owns) approximately 70 percent of the shares – an interest that (depending on the share price) is worth several hundred million euros. Co-name giver Streng is no longer in the company.

Import Iranian marble - (An elaborate Advance Fee Fraud!)

Outside of his listed company, Blijdorp is always looking for opportunities, say people who have worked closely with him. Such as the import of Iranian marble, which NRC reported on in January. In 2015, the media-shy tax-free entrepreneur stepped into exploiting nine Iranian marble quarries together with 34-year-old Iranian-Dutch Daniel M. Blijdorp lends Daniel around 70 million euros to acquire the quarry licenses. (An elaborate Advance Fee Fraud!)

The licenses and the loans would end up in a joint company from the profit Danial M. Blijdorp had to pay off. Things turn out differently: the duo gets into a heated argument, and Blijdorp puts his young partner under pressure to hand over the licenses to him. As a result, Danial would be left with a debt of millions, but without grooves. If Danial refuses, Blijdorp reports a scam. The Public Prosecution Service picked up the case and raids Danial's home in December 2019.

Read here the research story about Willem Blijdorp and the marble import: How a dream deal about Iranian marble degenerating into a mud fight

The case is explosive for both men. For Daniel M. because of the ongoing criminal investigation, for Blijdorp because of Daniel's accusation that he – among other things, through a smear campaign – has put the Public Prosecution Service in front of his cart. Blijdorp denies that in all keys.

After the publication about the marble shop, various former business partners of Blijdorp called and emailed NRC. They recognize the story of Daniel, who confidently embarks on the adventure and embraces Blijdorp as a financier, shareholder, and teacher. They also recognize the sequel: the brutal collision with Blijdorp, then tries to appropriate the valuable assets of the joint venture by creating financial pressure.

One of the men approaching NRC is 48-year-old Rotterdammer Martin N., who, with his family business Metco supplied shower and bath products to, among others, retail chain Action. He met Blijdorp in Spain in 2008 and built a good relationship with the B&S boss. "Blijdorp often came to me, was always curious about my work," says Martin. "I trusted him completely. I didn't realize at the time how close our trade was to his and that he saw me as a competitor."

I trusted Blijdorp completely. I didn't realize at the time how close our trade was to his and that he saw me as a competitor.

Martin N., owner of Metco

In March 2014, Martin wants to buy out one of his financiers. He approaches Blijdorp to take over his interest. For example, Blijdorp acquires half of the shares in Metco. After that, the relationship between the two men changes. Blijdorp tells Martin increasingly urgently that Metco is in dire straits and that he can better have his family business run by two people from Blijdorp.

When Martin refuses to make way, he gets into trouble at the end of 2016 with his house bank, Deutsche Bank, which suddenly does not want to renew its loans. Blijdorp – who boasts that the CEO of Deutsche Bank Nederland is a 'good friend' of his – has sent the bank an email suggesting that Metco has committed forgery. The bank cancels the loans and confiscates all stocks.

"Then it became clear what Blijdorp was after," says Martin. "He made a deal to buy Deutsche Bank's inventories for half the market value." Metco can no longer do business without stocks and financing. "After that, Blijdorp also had me declared bankrupt," says Martin.

Martin N. does win one lawsuit: in mid-2020, the judge ruled that Blijdorp's email with allegations to Deutsche Bank had a "rather speculative basis". That judgment gives Martin good chances to recover damages from Blijdorp through the courts, but his money has run out. Now he awaits his moment.

He is not the only loser in the Metco case. NRC also reports Raj Janardhan from Dubai, who has been in international trade for forty years – first with multinationals such as Unilever and Colgate, then independently. Metco was one of its best customers for six years, but that changed the moment Martin N. met Blijdorp, says Janardhan. "Willem seemed like a nice guy. During dinners in Dubai and Amsterdam, I told great stories about expanding and how I could also supply his other companies."

When things go wrong between Martin N. and Blijdorp, Janardhan discovers the other side of the B&S foreman. "What Blijdorp has done to Martin, I have never experienced," he says. "Normal people with business conflicts buy each other out, fight it out in court, or take their loss. But Blijdorp started a vendetta against Martin. He destroyed his life for no reason."

Blijdorp started a vendetta against Martin N. and destroyed his life for no reason.

Raj Janardhan trader who worked with Willem Blijdorp

Janardhan himself is also introduced to the business morality of Blijdorp. He had 494 pallets of shower cream in the Dutch warehouses Deutsche Bank had seized. Blijdorp did not want to release them, not even when Janardhan went to a Dutch bailiff to secure the goods (value: almost 300,000 euros). Instead, Blijdorp had the pallets removed from the warehouse. The police, Janardhan says, did not want to act. "They called it a business dispute." Janardhan, tired and fearful of rising lawyer's fees, gave up the fight. "Pure theft", he calls Blijdorp's performance.

Conflict with Jack Daniels

Janardhan could have been warned, say people who have known Blijdorp for some time. They point to a conflict between Blijdorp and whisky producer Jack Daniels over 20,000 bottles of whisky. Salient in this matter is a declaration by a Groningen bailiff, who, on 12 April 1999, wants to seize the whisky stored in Blijdorp's warehouses in Farmsum on behalf of Jack Daniels. The producer suspects Blijdorp of reselling the cheaper tax-free bottles with a big profit to Dutch liquor stores. Jack Daniels does not want A-brand bottles to come on the market like this and therefore have them seized.

When the bailiff arrives at Steenweg 17 in Farmsum, Willem Blijdorp awaits him. He threatens "with violence", as a result of which the bailiff has to flee, according to the declaration. When the bailiff returned with police later that evening, lawyer Paul Reeskamp, who counseled Jack Daniels for twenty years, "just saw how the bottles of whiskey were taken away in large trucks."

Where traders such as Martin N. and Janardhan did not pursue their case against Blijdorp, the whisky giant did have the money and patience to litigate for a long time. That paid off: at the beginning of 2020, after two decades of litigation, two subsidiaries of B&S were sentenced to infringement of Jack Daniels' trademark rights and compensation for some 1.5 million euros in damages, plus twenty years of interest.

Another case that continues to haunt Blijdorp is the one around the Zuiddijk marina in Zaandam, which has been his property since 2011. Previously, the marina near the North Sea Canal was in the hands of criminals through companies in Gibraltar and Belize. That changes when Blijdorp takes over the port from Rogé van de Weg, a convicted bankruptcy fraudster from the north of the Netherlands. According to the papers, Blijdorp pays about 1.3 million euros, which will never be on the table. It is crossed out against claims Blijdorp would have had on Van de Weg.

He later goes bankrupt and ends up in prison for fraud. His curator, Arie Brink from Leeuwarden, has been trying to recover the 1.3 million from Blijdorp for years now. Once, around the IPO of B&S in 2018, he is close to a comparison. But once the trading house has the stock exchange listing, the settlement will not go through anyway. "I feel like I've been kept on a leash," Brink says. "Probably because Blijdorp did not want to have any legal disputes around the IPO."

Franck Peyrard also feels "business murdered" by Blijdorp. The wine merchant from Lozanne, just above Lyon, is looking for revenge – but his resources have been exhausted after his battle with the Dutch multimillionaire.

In 2013, Peyrard partnered with Blijdorp to jointly realize Escale Grands Vins, a retail chain for exclusive wines and champagnes. This should be a separate sales channel for private individuals in addition to Peyrard's flourishing wholesale business – of which Blijdorp has been half-owner since 2011 through a French B&S subsidiary. But shortly after Blijdorp and Peyrard set up the retail chain, Blijdorp demands that his partner deliver his chic products to the French hypermarchés. If Peyrard refuses, the Dutchman "turned into the devil," says the Frenchman.

Peyrard tells how he was then financially driven into the corner by Blijdorp and gave up his shares to the Groninger under pressure. A week later, four Dutch trucks and several haulers suddenly appear at the door, local newspapers from that time report. The entire wine warehouse is loaded, after which Escale Grands Vins goes bankrupt.

Bigger and more unpredictable

Conflicts with (former) business partners, long-running lawsuits, and accusations of fraud – Blijdorp is used to something in his long entrepreneurial history. But the last case he ended up in, against marble entrepreneur Daniel M., is different: bigger, more complicated, and more unpredictable.

Unlike entrepreneurs such as Janardhan, Peyrard, and Martin N., the young Iranian-Dutch marble merchant does have the time and the means to resist. Assisted by a small army of lawyers, Daniel M's has conducted dozens of legal proceedings in recent years – also against Willem Blijdorp. Daniel's lawyers use information about the B&S boss's past in their proceedings in the hope of showing that there is a pattern in Blijdorp's behavior.

It is questionable whether that matters for Daniel M's case, but Blijdorp's disillusioned ex-business partners are happy that his history is being revealed. And that they are not the only ones who feel taken in by the B&S foreman. They are also hopeful: now that light is shining on this side of Blijdorp, they see for the first time a chance, however small, of justice. Because sooner or later, says wine merchant Franck Peyrard, everyone has to be accountable. "Also Willem Blijdorp."

----

REACTION

'DOES NOT RECOGNIZE ITSELF'

This article is based on court documents and legal files, cadastral data, information from the Chamber of Commerce and similar foreign registers, public publications, and conversations with data subjects. The statements of the aggrieved entrepreneurs Martin M, Janardhan, and Peyrard have been verified as much as possible based on formal documents.

Willem Blijdorp says through his lawyers that he will not respond to a series of substantive questions about incidents and quotes from former business partners described in this article. However, his lawyers say that Blijdorp "does not recognize himself in the picture sketched of him".

What may play a role in this reaction is a series of ongoing legal proceedings between Willem Blijdorp and Daniel M, with 70 million euros from Blijdorp as a bet.

https://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2022/03/04/de-twee-gezichten-van-willem-blijdorp

Iranian-Dutch natural stone traderi has to repay the more than €75 million he borrowed in 2015 and 2016 from the Dutch multimillionaire Willem Blijdorp 'immediately', with 4.5% interest. This verdict, published on Thursday, points to the Amsterdam court in a protracted dispute between the quarreling former business partners.

The hectic pace of recent years at the listed B&S does not seem to have done the relationship with accountant Deloitte any good. It seems that Deloitte will stop as the wholesaler's book inspector. The search for a successor is still ongoing.

B&S has kept investors in suspense over its full-year results for seven weeks longer than planned. An internal investigation into possible misconduct has been completed, the accountant has signed the figures and the company has found a new CEO. But to allay investor doubts, B&S must dispel the hint of conflict of interest that haunts the company.

A loss of more than $13 million at B&S in Dubai, where a son of Quote 500 member and owner Willem Blijdorp is sales director, triggered the current governance crisis at his listed tax-free empire. This is evident from research by Quote.

A state of emergency has been declared at the listed wholesaler B&S. The CEO leaves immediately and major shareholder Willem Blijdorp gives up his supervisory position. In addition, an internal investigation found that B&S officials overstepped the mark in some related party transactions. And then there is another loss of millions because B&S does not get a bill paid.

Bad debts

B&S did release its fourth-quarter figures for last year on Monday, in which it made a provision of $6 million. This is in addition to the $7.5 million that wholesalers had already taken in the first half of the year for a so-called 'bad debt'. There is also a second bad debt, for which a provision of up to $3.4 million may have to be taken.

Lawyers of ex-billionaire Willem Blijdorp sent private detectives after another lawyer.

Private detectives had to observe a former resident lawyer of Blijdorp and his company B&S.

Blijdorp lawyers also seized all information in the office of the former house lawyer.

B&S divisions Kamstra and PHI traded inverted blood tests according to the court in The Hague.

An unpublished judgment shows that the companies must hand over illegally obtained profits.

The reseller of the counterfeit packaging tests, H&H Wholesale, must pay US $26.5 million in damages.

According to the court in The Hague, companies of the listed Dutch wholesale group B&S are guilty of illegal international trade in counterfeit blood tests.

Willem Blijdorp, the big man behind the B&S stock exchange fund, appears to provide large mortgage loans to the cultural elite and convicted money launderers through a foundation. The Vereniging van Effectenbezitters believes that B&S should have reported this because Blijdorp owns 67% of the shares of B&S. 'You want to know from him in what kind of environment he operates in business, whether dependencies are created.'

The CEO of B&S received a million-dollar loan from the vice-chairman of the supervisory board. This is not in the annual reports.

In brief

- B&S withholds a loan of millions that the CEO received from Commissioner Willem Blijdorp.

- The CEO's private home serves as collateral for the loan.

- It gives 'the appearance of a potential conflict of interest', says investor club Eumedion.

- United Against Nuclear Iran denounces Iranian interests B&S CEO Blijdorp.

- US watchdog speaks of 'clear violation of Iran sanctions'.

- UANI is led by leaders such as Joseph Lieberman, Jeb Bush, John Bolton and ex-Mossad chiefs.

- Nine employees of the B&S were involved in Iranian investments by CEO Willem Blijdorp.

- Lawyers warned him of the risk of his Iranian interests violating sanctions.

- Investors' association VEB denounces the entanglement of B&S interests with private affairs of the CEO.

Investigate Business Quarrel

A Dutch-Iranian entrepreneur from a village in North Holland and a Groningen multimillionaire join forces to exploit marble quarries in Iran. It seems like a golden deal – but then they get into a fight.

(An Elaborate Advance Fee Fraud)

Mr Blijdorp, a major shareholder, co-founder and deputy chairman of listed group B&S in Holland, has been locked in a years-long battle with former business partner Daniel M. after the two men had a falling out.

Clinuvel Pharmaceuticals - a market darling which has developed a drug for a rare skin disease for which it now faces competition from a Japanese rival - is facing a second strike and possible spill at its annual meeting.

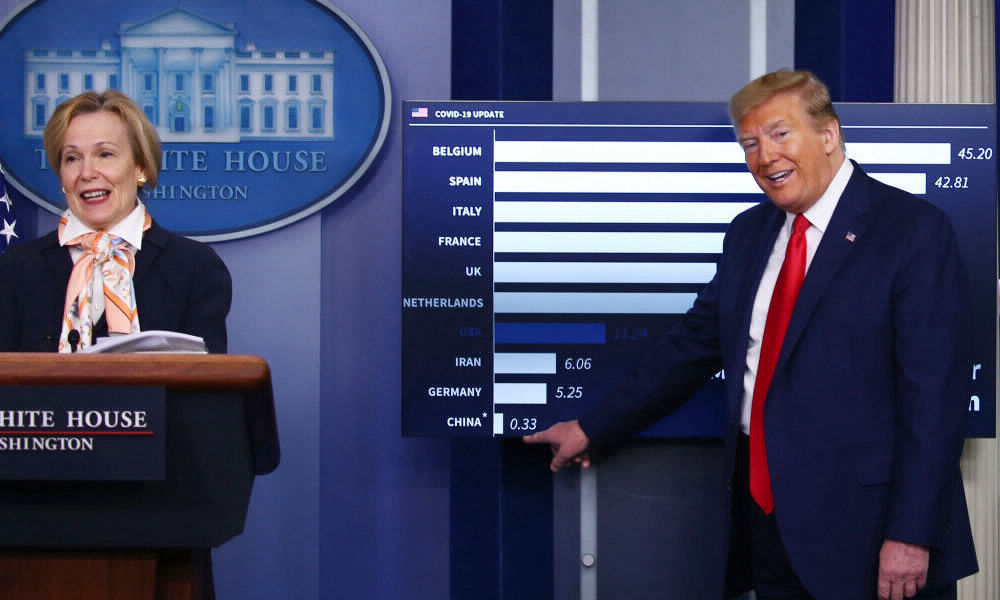

Briefings regarding the pandemic. “the numbers and data the task forces worldwide have put out – as they also say not complete – are not accurate and therefore are misleading,”. “Close to all cases admitted to IC’s are classified as corona related."

Following Birx’s chart of statistics Saturday at the press briefing, Engelsman noted that “getting facts right is important to make sure history is not distorted or placed in the wrong context.”

“I do not remember when the first numbers to establish a baseline are skewed from the beginning,” Engelsman said of Birx’s statistics provided to American citizens.